St Osyth and the Shadow of Witchcraft in England

While the infamous Salem trials often dominate popular consciousness, the United Kingdom experienced its own dark chapters, with communities gripped by paranoia, creating devastating consequences for those caught in its wake. Among these grim episodes, the Witch Trials of St Osyth, a picturesque village on the Essex coast, stand out as a particularly stark and poignant example.

St Osyth, like many English communities in the 16th century, was susceptible to the prevalent anxieties surrounding witchcraft. In an era where life was precarious, with disease, famine, and sudden misfortune common, people desperately sought explanations for suffering. When livestock died inexplicably, when crops failed, or when illness struck, the finger of blame often pointed to those on the fringes of society, or those who possessed an unusual knowledge of herbs, sharp tongue or a poor social reputation. Witchcraft became a convenient scapegoat for every ill.

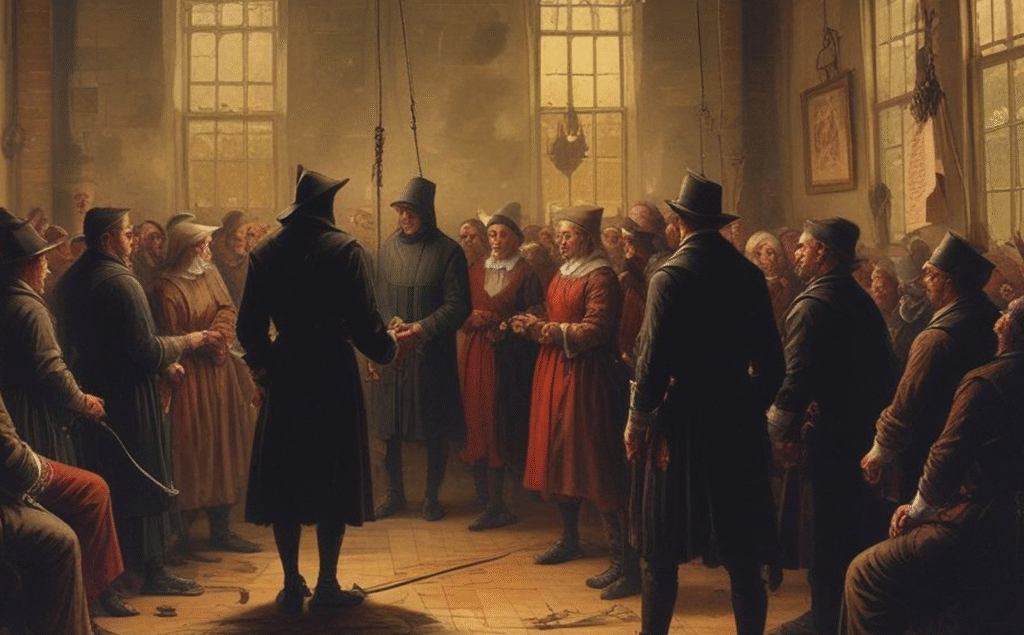

The Cage: A Symbol of Torment in St Osyth

Central to the narrative of the St Osyth trials, and indeed a chilling artifact of the era, is The Cage. This imposing structure likely served as a grim holding cell for those accused of witchcraft before their examination and potential trial. Imagine the terror of being confined within such a cold desolate space, hearing the whispers of villagers outside, fueled by fear and suspicion. The Cage was not merely a prison; it was a psychological weapon, designed to break the spirit and extract confessions.

The trials in St Osyth, which occurred primarily in 1582, were not isolated incidents. They were part of a wider trend across England. While the scale of executions might not have rivaled some continental European countries, the fear was no less potent. Accusations often arose from personal disputes, soured trade attempts, or the simple misfortune of being disliked. Confessions were often coerced through unethical examination techniques, including deception and using child testimony. This would only become fuel to feed the flames of persecution.

Ursula Kemp and St Osyth’s Accused

The 1582 St Osyth Witch Trials saw several individuals accused of consorting with demonic familiars and causing harm through their supposed magical abilities. While the historical records are often one-sided, a picture emerges of a community fractured by fear and betrayal.

At the heart of these accusations was Ursula Kemp. A woman of poor local repute, Ursula was a healer and cunning person, possessing knowledge of herbs and folk remedies. In a time when access to formal healthcare was limited, women like Ursula were vital to their communities, offering comfort and relief from suffering. However, this very knowledge, could also be twisted into something sinister in the eyes of the fearful.

Ursula was accused of consorting with demonic familiars, and thus causing illness and death to other villagers. It was alleged that she had four familiars, a demon in animal form, which aided her in her nefarious acts. The accusations were likely amplified by her poor social standing and perhaps a perceived lack of conformity to societal expectations. In a patriarchal society, a woman such as Ursula could easily become a target for suspicion.

Other women accused alongside Ursula faced similar allegations:

- Ales Newman: Accused of sending demonic familiars to attack livestock and people.

- Elizabeth Bennet: Possessing familiars and using them to hurt or kill others.

- Ales (Barnes) Hunt: Killing livestock and a person with bewitchments

- Annis Glascock: Murdering through bewitching.

- Margerie (Barnes) Sammon: Inheriting and holding demonic familiars.

Fear would also spread through neighboring communities, seeing women (and one man) from neighboring town’s also dragged into the hysteria, being accused of Witchcraft. Joan Pechey, Cisley Selles, Henry Selles, Ales Manfield, Margaret Grevell, Elizabeth Ewstace, Margaret Ewstace, Joan Robinson and Annis Heard would also face the terror of such accusations against them.

The examinations, overseen by the local Justice of the Peace, Brian Darcy, would have been deeply intrusive and terrifying. Deceptive techniques were used to farm confessions and further accusations, with children used for testimony and women’s bodies searched for “witch’s teats” being used as evidence to build cases.

Legacy of the St Osyth Witch Trials

Ursula Kemp, along with Elizabeth Bennet, was ultimately hanged in Chelmsford, as a result of their trials at the Chelmsford Assizes. Sadly, a further four of the accused who escaped the hangman’s noose, would perish in the harsh confines of the Colchester Castle dungeon, where they had been held as long-term prisoners.

The story of Ursula, and each of the others accused, serves as a stark reminder of the dangers of mass hysteria and the devastating consequences of unchecked fear and superstition.

The St Osyth trials, though perhaps not as widely publicized as some others, are a crucial piece of the larger narrative of witchcraft accusations in England. They highlight:

- The role of women: The majority of those accused and executed for witchcraft were women, often those who were elderly, poor, widowed, or unmarried – individuals who were already marginalized.

- The impact of local disputes: Many accusations stemmed from petty quarrels, neighbourly disputes, or perceived slights.

- The power of confession: Forced confessions, however unreliable, were often the only “evidence” needed to secure a conviction.

- The enduring legacy of fear: Physical remnants, like The Cage, continue to serve as tangible, haunting reminders of a period when fear could condemn individuals to the most brutal of fates.

Today, St Osyth is a tranquil village, its history a blend of maritime charm and the darker undertones of its past. The Cage stands as a silent testament to the courage of those who endured such persecution and a somber warning about the dangers of allowing fear to cloud judgment and destroy lives. The whispers of the past still echo deep, reminding us of the importance of empathy, reason, and the protection of the vulnerable.